Red Ball Express (cont.)

I Drove on the Red Ball Express

by Mearl R. Guthrie, Co. B 407th Infantry

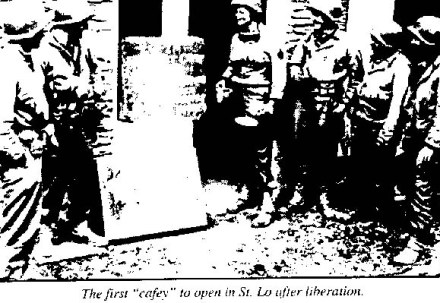

After the 102nd landed at Cherbourg, the first division to go to Europe without stopping in England, we pitched pup tents in muddy potato fields near Sainte Mere Eglise. The days were spent hiking through the small towns and the countryside along the coast. We stopped to examine many of the German fortifications overlooking the English Channel. There were many supplies left in the pillboxes. One of our favorite pastimes was to take a case of German potato mashers (hand grenades) to the top of the pillbox, pull the cords and throw the grenades toward the beaches. Sometimes French citizens would appear to see if the war had returned. Sleeping in a pup tent in the mud is interesting if not impossible. One day an officer showed up in our area and asked if anyone would volunteer to drive a truck on the Red Ball Express. He said the Army would train you to drive a truck. It sounded a lot better to live in a dry truck rather than in a wet, muddy tent. I volunteered, one of the few times in my army career of 39 months active duty and seven years in the Reserves. As I remember, the training was to put two men in a truck with the order to follow the truck in front of you. We drove constantly for two plus weeks from Cherbourg to Versailles just outside Paris. Our route took us through St. Lo which the Americans had completely destroyed with bombs and artillery. A road had been bulldozed through the rubble. We would stop for 10 minutes every two hours for you know what and perhaps a snack. Our snacks consisted of cans of C rations. K-rations and 10-in-ones had not arrived on the scene at that time. We stopped in a couple of little towns that had cafes and some of us would heat the C-Rations on the manifold of the truck. We were young and hungry so we ate whatever we had. On one occasion, we liberated a case of oranges at the dock, but ended up giving them to young, hungry French children who had never seen an orange before. Theft of the five tons of supplies on the 2-1/2 ton trucks was always a possibility by hungry Frenchmen, black-marketers, and our own troops who needed (or wanted) food, ammunition or gasoline. Wooden boxes with a corner painted green held PX rations. When our truck carried these boxes one driver hopped up on top at each stop with his M-1 ready. One time an officer stopped our convoy of 20 trucks and told the lieutenant in charge that Gen. Patton needed our load of gasoline delivered to a town on the other side of Paris. I don’t recall any particulars, but I think we delivered our load to the depot at Versailles for delivery by the next convey to the frontlines. We saw a few German planes and generally stopped and headed for the bushes. if they flew toward us. One time I was on a truck with a 50-caliber machine gun mounted on a 360′ track above the cab. There were two or three convoys stopped. Three machine guns shooting together brought down one German plane. There was one experience on the Red Ball I will never forget. At the bottom of a very steep grade on the route, there was a 90′ right turn in the road. We usually carried five tons of supplies on the 2-1/2 ton trucks and you had better shift into low gear at the top of the grade if you expected to get around that curve safely! One time, late in my two-weeks career on the Red Ball, I was asleep and my buddy was driving with one day’s experience. I awoke because the truck was weaving back and forth down that steep grade in high gear. I never knew how my buddy made it around the curve without turning over, but he did. On all future trips I made sure I was driving when we reached the stretch of road with the steep grade. Many experts have suggested that the Red Ball shortened World War II considerably. I’m proud to have been a part of that military strategy to get the necessary equipment and supplies to strategic points for use by the troops on the front lines. After returning to our tents, the men in the division rode in boxcars into Belgium. We spent the next seven months in our struggles to reach the Elbe River, where we waited for the Russians. I joined the 102nd at Camp Swift, Texas and stayed with them all the way to the Elbe River, through the Occupation, and came home with the division in February 1946.

See the equipment that was used on the Redball Express

Where: US ARMY TRANSPORTATION MUSEUM FORT EUSTIS, VIRGINIA

Fort Eustis is near the Hampton Roads area.

Also, near Jamestown, Yorktown, Williamsburg Historical Areas.

In addition to the equipment, there is video taken in France in 1944.

There is a selection of books and articles about the Redball.

On a Red Ball trip from Omaha Beach to Paris, I pulled into a lighted warehouse and the first thing I saw was a Major pacing the platform screaming; “ViVa Le France, kick them in the pants. They stole the train!” I had the idea that a supply train had been stolen, but my truck was unloaded and I returned to Normandy without ever hearing the entire story.

George Cronin, 407th Company F

The Red Ball Express was a massive convoy effort to supply the Allied armies moving through Europe. It was the most important factor in the rapid defeat of the German Army. General Bradley wrote “On both fronts an acute shortage of supplies governed all our operations”, “Some twenty-eight divisions were advancing across France and Belgium. Each division ordinarily required 700-750 tons a day, a total daily consumption of about 20,000 tons.” This gives you some idea of how much ordinance was needed to supply the front. Patton’s tanks were soon grinding to a halt from lack of fuel and ordnance. The Red Ball Express was conceived in a 36-hour brain storming session. The name came from the railroad phrase to “red ball” or to ship it express. The Red Ball Express lasted only three months from August 25 to November 16, 1944. But with out the Red Ball Express the campaign in the European Theater would have dragged on for years. Also the extraordinary mobility of the allied forces would have be drastically limited. The Red Ball Express was created to bring ordinance and gas to the units fighting at the front. In late July the German front cracked. Allied forces rushed through the gap in the line. Running towards the Seine River in pursuit of the German Seventh Army. The high command had not anticipated the speed of the German retreat. They though that the battles would have been a slow steady roll-up the of the enemies divisions. The key to pursuit was a continues supply of fuel and ordinance. Thus leading to the development of the Red Ball express. At the peak of it’s operation it operated 5,958 vehicles, carried 12,342 tons of supplies to forward depots. To begin with there were not enough trucks or divers. The army raided any units that had trucks and used them to form the provisional truck units for Red Ball. Any solider that duties were not critical to the immediate war effort were asked to become divers. They also principally used blacks because they were not used in the combat at all. A volunteer, Phillip Dick, had never driven a truck before in his life was told this was not a problem by the army. He was simply given an hours instruction and told he was qualified. The first convoys quickly bogged down in civilian and military traffic. In response, the army established a priority route that consisted of two parallel highways between the beachhead and the city of Chartes. The northern rout was for outbound traffic the southern route was for returning traffic. All civilian and unrelated military traffic was forbidden on these routes. There is a story of a small French car sneaking onto the Red Ball highway and getting crushed between two trucks. The army went to great lengths to control the Red Ball express. The rules sheets still survive today. Trucks were to travel in convoys. Each convoy was to have no fewer then five trucks each. Each truck was to have a number marking its position in the convoy. There were to be a lead and follow jeeps. The trucks were to stay 60 feet apart and travel at 35 m.p.h. Nevertheless, the fast moving front caused the rules concerning the supply of troops to be thrown out the window. The real story of the Red Ball Express was often more like a free-for-all at a stock car race. Divers quickly learned to strip the governors off the trucks, which sapped the overloaded vehicles of much needed power to climb hills and prevented them from sustaining a steady and higher speed. The longest waits for the Express was most often the occurred when they were being loaded. If they waited for a convoy to assemble they could be delayed for hours. Most trucks when out on their own to keep the supply line going. Sleep was a major problem. Most often when a truck drifted out of a convoy it was because they had fallen a sleep at the wheel. When convoys stalled for short periods, their drivers dozed, their heads slumped over the wheels. A jolt form the leading truck backing up to hit your bumper told you that it was time to get up and go. There where commanders who went by the book. A 2 1/2-ton truck could carry a load of no more that 5 tons. The army had authorized trucks to carry twice there normal load, but one layer of 105mm and 155mm artillery shells put the truck over the weight limit. Most Quartermaster officers however ignored weight restrictions and sent the trucks out overloaded. Armies where sometimes so desperate for gasoline and ammunition that they sent out raiding parties to “liberate” supplies before they got to the depot. Often the front was moving so fast that the Red Ball Drivers never found their destination. It was not unheard of for drivers to hawk the loads to anyone interested. They always found takers. Most often trucks carried supplies form one depot to the next. From the advanced depots more trucks picked up supplies and carried them farther or to the front lines. Shortly after the break out at Normandy, it wasn’t too uncommon for Red Ball trucks to drop Ammunition at artillery positions within a few miles of the front lines. One Red Ball Driver remembers driving right up to a stranded Sherman tank and Passing Jerrycans of Gas to the Crew while Germans where a stone throw away. Gasoline could be sold on the French black market for $100. There where always guards posted at the trucks to prevent war-weary French and profit minded Americans from taking anything not tied down. MP’s were stationed at the crossroads to prevent tucks from getting lost. But even if there were no MP’s there were always signs with a big Red Ball with arrows pointing the way. Also the convoy directors always carried maps. Engineers constantly patrolled the highways for battle damage and broken down trucks. The used the Diamond T Prime Mover. It was strong enough to pull a fully loaded 6 by 6 back to a repair station. Tucks were instructed to pull over and wait for a wrecker when their trucks broke down. The Red Ball Trucks took a tremendous beating. Batteries dried up, engines overheated, motors burned out for lack of grease and oil, bolts came loose, transmissions were overstressed, and drive shafts fell off. After the first month of operation, the Red Ball Express wore out 40,000 tires Most where retread and came back glued and taped together. The biggest problem was carelessly thrown away ration tins that littered the highways. Red Ball Express trucks were most often stopped by water in the gas. Sometimes it was lack of maintenance, but sabotage was a factor. German prisoners of war were aware that the Achilles’ heal of the 6-by-6 was water in the gas, POWs were frequently used to load supplies in the rear areas and the fuel the trucks. Many a Red Ball Driver can recall seeing POWs dragging jerrycans through snow and rain with the caps wide open trying to contaminate the gas. POWs were loaded on to the back of the trucks and shipped back home. So too were artillery casings, jerrycans, and sometimes soldiers that had been killed in action. Transporting the dead was a particularly dreadful task. The stench from the bodies took days to dissipate. The truck beds had to be washed down, but that didn’t always get the blood and grime that seeped between the cracks of the truck bed. The Red Ball Express drivers were seldom in combat. But there was always the ever-present danger of being strafed by German fighters. First Lieutenant Charles Weko remembers being strafed by German planes. Weko first believed that it was some one throwing stones at metal. Realizing the danger he leapt from his truck. Some of the trucks had 50 caliber guns mounted on their cabs. Some of the men jumped to one of the guns and brought down one of the planes. Drivers were to wear helmets and carry rifles, but the helmets most often wound up on the floor next to the rifles. Also drivers sand bagged the floor to stop mine blasts. Many Red Ball Jeeps were equipped with hooks to catch any piano wire that had been strung across the highway. Most of the jeeps and trucks drove with their windshields down. This was mostly because a glint off a windshield would bring down a hale of German artillery fire. White and African Americans were not urged to mingle during off duty hours. “You accepted discrimination” recalls Washington Rector of the 3916th Quartermaster Truck Company. “We were warned not to fraternize with whites for fear problems would arise.” The races were sufficiently separated that even today some white Veterans where black. Emerik remembers informing a solider that he was a Red Ball driver. The soldier then asked him why he was not black. The Red Ball Express was officially terminated on November 16, 1944, when it had completed it mission. New Express lines were formed with different names. Colonel John S.D. Eisenhower wrote: “The Spectacular nature of the advance [through France] was due in as great a measure to the men who drove the Red Ball trucks as to those who drove the tanks.” “With out it the advance across France could never had been made.”

Mearl R. Guthrie, Red Ball Coordinator, 407B

The Red Ball Express was the codename for one of World War II’s most massive logistics operations, namely a fleet of over 6,000 trucks and trailers that delivered over 412,000 tons of ammunition, food, and fuel (and then some!) to the Allied armies in the ETO between August 25 and November 16, 1944. For the 225th AAA Searchlight Battalion, which was a semi-mobile outfit, being a “Red Ball” trucker meant that you were charged with driving battalion trucks to the Red Ball depots and picking up supplies, especially gasoline and ammo, and then ferrying them back to the 225th’s positions at forward airfields along the West Wall. Though you didn’t make the long hauls from Normandy into eastern France and Belgium, you kept the battalion supplied as a last, vital hop in the supply chain. The introduction of motorized vehicles and equipment at the beginning of the 20th Century has changed forever the face of battle. Since the time of Alexander the Great large armies have crossed the world’s military landscape with ponderous difficulty, their seemingly endless lines of animal-drawn carts and wagons trailing far behind. How different this is from the pace and dimension of modern warfare. The highly mechanized U. S. Army of WW II had the ability to cover vast distances at speeds unimagined by even the greatest of the Great Captains of old. That speed brought with it a need for new forms of fuel — in prodigious amounts to keep the engines of war running. Quartermasters who for centuries gathered huge stockpiles of hay, barley, and oats to “fuel” past armies on the move, were now required to supply the petroleum, oil and lubricants (POL) that make up the U.S. Army’s logistical lifeblood. The Army had begun serious experimentation with gasoline-driven trucks and automobiles as early as 1911. In 1916, during the “Punitive Expedition” to Mexico, trucks were first used in a tactical setting by American troops abroad. When the United States declared war on Germany the following year, Pershing took hundreds of motorized vehicles and equipment with him to France. This action spawned a huge, new appetite for POL. Though the fighting on the Western Front was relatively static, petroleum played a decisive role. It was, according to Clemenceau, “as necessary as blood.” The French expression “le sang rouge de guerre” “the red blood of war,” captures the significance of gasoline in modern war fighting. Said Churchill afterwards, we (the Allies) floated to victory “on a sea of oil.” All told, the American Expeditionary Force consumed nearly 40 million gallons of gasoline in World War I. This was an immense amount for the time, a mere fraction of what it would take to defeat Hitler’s Germany a generation later. World War II was the first truly mechanized war, or as one observer put it, a “100 percent internal combustion engine war.” It placed unprecedented demand on Army Quartermasters for POL support around the world. Even the relatively small North African campaign of (code-named Operation TORCH) required no less than 10 million gallons of gasoline. Allied logisticians pushed the red stuff forward over the beaches and across parched deserts using five-gallon “blitz” cans, tanker trucks, and miles of newly designed portable pipelines. This experience, coupled with the Sicilian and Italian campaigns that followed, served as a warm-up for the Normandy Invasion of June1944. The cross-channel invasion known as Operation OVERLORD followed months of intensive preparation. During that time Allied logisticians in England worked out a detailed plan for POL support on the continent. All vehicles in the assault were to arrive on the beachhead with full tanks, carrying extra gasoline in five-gallon jerricans. Packaged distribution was to continue throughout the operation’s initial phase (D-Day to D+41). Planners predicted a fairly slow-paced offensive thereafter, allowing for systematic construction of base, intermediate, and forward area depots. In the meantime, it was hoped that the early capture and development of Cherbourg’s port facilities (by around D + 15) would enable combat engineers to begin laying three six-inch pipelines inland toward Paris. Much depended upon the success of this operation. Pipelines were expected to eventually move about 90 percent of all POL entering the European Theater quickly and efficiently to forward area terminals or transfer points. Operation OVERLORD was officially scheduled to terminate on D + 90 with the forward line hopefully anchored on the banks of the Seine. The post-OVERLORD period (D + 91 to D + 360) would have the Army pushing steadily eastward to the Rhine, where it was assumed a final showdown would take place. From start to finish, planners expected well-placed bulk maintenance facilities to carry the lion’s share of POL support. On D-Day itself events occurred much as planned from a POL perspective. The first assault vehicles rolled ashore and immediately began stacking their cargoes of five-gallon cans. They were placed in small, widely scattered dump sites throughout the lodgment area. This simple method of open storage made Class III supply easily accessible. At the same time, this storage method rendered Class III supplies less vulnerable to enemy attack. By the end of the first week (D + 6) Quartermaster petroleum supply companies were on hand to begin moving these stores away from Omaha beach as the buildup continued. German defenders fought tenaciously but failed to turn back the Allied assault. By the end of June, the beachhead had expanded considerably. Allied combat units were rushing headlong in the infamous hedgerows some 25 miles beyond to engage in a bloody slugfest that lasted several weeks. The Allies’ inability to score a quick breakthrough anywhere along the line had both positive and negative effects on the supply situation. Since there was so little forward movement, reserve stockpiles grew at an accelerated pace. Approximately 177,000 vehicles and more than half of a million tons of supplies came ashore by D + 21. POL reserves at that time topped 7.5 million gallons. On the other hand, failure to capture Cherbourg as early as planned meant that the proposed pipeline schedule had to be voided. For weeks to come, all POL requirements would have to be met solely by packaged distribution. A breakout finally occurred the last week of July. Following a massive aerial bombardment on the 25th, General Bradley’s First Army managed to rupture German lines to the right of St. Lo. The next day, three armored divisions poured rapidly through the gap and moved 25 miles south near the base of the Contentin peninsula. With the door forced wide open, new opportunities for early tactical success abounded. There was a chance that if the Allies moved fast, struck hard and pressed the fight, they might quickly defeat the entire German Army in France. In light of this largely unforeseen possibility, many of the pre-invasion plans were summarily scrapped. First and Third Armies joined forces on 1 August (to form the U.S. 12th Army Group) and at once began exploiting the principle of maneuver warfare to the fullest. The Germans offered even lighter resistance than expected. Success followed success in the Allied pursuit across France. As Patton’s Third Army swept westward into Brittany and south to Le Mans, it burned up an average of more than 380,000 gallons of gasoline per day. By 7 August (a week after becoming operational) its reserves were completely exhausted. Patton had to rely on daily truck loads of packaged POL from the rear. Nevertheless, he managed to continue this highly mobile type of warfare, driving eastward for another three weeks, before being halted by critical shortages of gasoline. Logistically speaking, the real turning point in the campaign came during the week of 20 – 26 August. At that time, elements of both the First and Third Armies were simultaneously engaged in rapid pursuit. They developed an insatiable thirst for gasoline, and consumed more during this one week than any time previously. Average consumption was well over 800,000 gallons per day. The First Army alone (with about 60 percent of its total supply allocations made up of Class III type items) used 782,000 gallons of motor fuel on 24 August. The next day Allied forces closed in on the Seine and columns of U.S. And French troops entered Paris. The decision to cross the Seine and immediately continue eastward, without waiting to more fully develop lines of communication, constituted a major departure from the OVERLORD plan. It posed serious difficulties for the theater logisticians, but was a gamble senior commanders were willing to risk. “The armies,” said General Bradley, on 27 August, “will go as far as practicable and then wait until the supply system in rear will permit further advance.” Once across the Seine, forward divisions not only extended their lines, but fanned out in every direction creating a front twice as broad as previously. The strain on the supply system was immediately noticed as deliveries slowed to a trickle. The late August – early September operations were described by war correspondent Ernie Pyle as “a tactician’s hell and a quartermaster’s purgatory.” Indeed It was both. Believing victory to be firmly within their grasp, the fast-moving armies had outrun their supply lines and were forced to live hand-to-mouth for several days. Ninety to ninety-five percent of all supplies on the continent still lay in base depots. In the vicinity of Normandy the First Army had in effect “leaped” more than 300 miles from Omaha beach in a month’s time. Third Army had done likewise. With the situation becoming daily more critical, it was time to begin what one historian labeled ‘frantic supply.” In a desperate effort to bridge the gap between user units at the front and mounting stockpiles back at Normandy a long distance, one-way, “loop-run” highway system — dubbed the Red Ball Express — was born. Since circumstances allowed little time for advance planning or preparation, Red Ball was, as one observer noted, “largely an impromptu affair.” It began on 25 August, with 67 truck companies running along a restricted route from St. Lo to Chartres, just south of Paris; and reached a peak four days later with 132 companies (nearly 6,000 vehicles) assigned to the project. Communications Zone (COMMZ) and Advance Section (ADSEC) transportation officials were responsible for overseeing Red Ball activities, but it required the support and coordination of many branches to succeed. While the Engineers were busy maintaining roads and bridges, MPs were on hand at each of the major check points to direct traffic and record pertinent data. Colorful signs and markers along the way — not unlike the old Burma Shave signs that covered America’s own countryside — kept drivers from getting lost, and at the same time publicized daily goals and achievements. Quartermasters truck drivers, materiel handlers, and petroleum specialists were ever present both along the route and at the forward-area truck-heads. Disabled vehicles moved to the side of the road, where they were either repaired on the spot by roving Ordnance units or evacuated to rear-area depots. Round-the-clock movement of traffic required adherence to a strict set of rules. For instance, all vehicles had to travel in convoys and maintain 60-yard intervals. They were not to exceed the maximum speed of 25 mph and no passing was allowed. After dark, Red Ball drivers were permitted the luxury of using full headlights instead of “cat eyes” for safety reasons. At exactly ten minutes before the hour each vehicle stopped in place for a 10-minute break. Bivouac areas were set up midway on the roads so exhausted drivers could get some rest and a hot meal. (Incidentally, most drivers soon picked up on handy tricks that come from living on the road, such as how to heat C-rations on the manifold or make hot coffee in a number-10 can using a bit of gasoline.) At its height the Red Ball saga captured the media’s attention, and had the effect of placing supply and service personnel in the spotlight for a change. Still, the job was hardly glamorous, involving as it did endless hours of dull, hard, and sometimes dangerous work, POL occupied prominent space on the Red Ball Express. In late August, Eisenhower decided to forward most petroleum supplies to the First Army (Hodges) and the British 21st Army Group (Montgomery). This action was to come at the expense of Patton’s Third Army to the South. On 31 August, Patton’s daily allotment of gasoline dropped off sharply from 400,000 to 31,000 gallons. This placed a virtual strangle hold on the fiery commander, who fumed, pleaded, begged, bellowed and cursed accordingly — but to no avail. “My men can eat their belts,” he was overhead telling Ike at a meeting on 2 September, “but my tanks gotta have gas.” The logistical crisis threatened to halt the Allies where the enemy could not. Fortunately, that crisis proved to be short-lived. It would only be a slight exaggeration to say that Red Ball saved the day. The hastily conceived system served as a useful expedient for bringing Class III items, especially gasoline, quickly to the fuel-starved front. Even though First and Third Army supply officers would continue bemoaning the gas shortage, the situation got markedly better. By the end of the first week in September, forward area truckheads were issuing POL as soon as it came in, and consumption rates were once again hitting the 800,000-gallon-a-day mark. The worst of Patton’s gasoline woes ended almost as quickly as they had begun. Mid-September saw the two American Armies issuing in excess of one million gallons of gasoline daily — enough to meet the immediate needs and begin building slight reserves. Red Ball was scheduled to run only until 5 September, but continued through mid-November. In all, it transported more than 500,000 tons of supplies. The system moved fuel quickly, if not always efficiently, to where most needed to keep the drive alive. Most importantly, the Red Ball Express brought precious time for the rear echelon support team, allowing it to complete its task of building up the railroads, port facilities, and pipelines needed to sustain the final drive into Germany. For over two months, the Red Ball Express did a magnificent job transporting petroleum over distances up to 400 miles. Quartermasters did their part by operating effectively as retailers of this product. However, success came with a price tag. Round-the-clock driving strained personnel and equipment. Continuous use of vehicles, without proper maintenance, led to their rapid deterioration and ultimately to a drain on parts and labor. Tire replacement alone nearly doubled from 29,142 just before Red Ball was launched to 55,059 in September. The situation was aggravated by driver abuse, such as speeding, and habitual overloading. Extreme fatigue also led to increased accidents, and even a few instances of sabotage, where drivers disabled their vehicles in order to rest. Red Ball proved beyond a doubt the versatility and convenience of transporting gasoline in small five-gallon containers. Jerricans required no special handling apparatus and were amenable to open storage without harmful effects. However, at the very height of Red Ball activities forward movement of POL was threatened by a severe shortage of jerricans. The cans were carelessly discarded from the beachhead area and littered the route all the way to the front. The Chief Quartermaster’s highly publicized propaganda blitz and cash incentive program prompted local civilians to help round up “AWOL” jerricans.” Still a jerrican shortage remained in effect until more cans were manufactured on the home front. Finally, the Red Ball Express had an inherent problem in that it was fast approaching a point of diminishing returns. As the route got longer and longer, the Red Ball required more gasoline — ultimately as much as 300,000 gallons per day — just to keep the Red Ball vehicles themselves moving.

Portions reprinted by permission from “POL on the Red Ball Express” by Dr. Steven E. Anders, Quartermaster Professional Bulletin, Spring 1989.

Red Ball Experience, by Rock King

Edited by Mearl R. Guthrie, Red Ball Coordinator

I was in Hq. Battery, 380 FA, assigned to the wire section, but trained to be a backup for the various fire direction jobs, as the T.O. provided only one man per job, and in combat, hours on the job were much too long. Also, it was a sensitive position. We landed in Normandy in September and encamped in the hedgerows waiting for orders. We’d been there about three weeks when they asked for volunteers to help drive trucks on what we learned was the Red Ball Express. I volunteered, to get away from KP, standing guard, and digging slit trenches for latrines. I was assigned to be the assistant to David Twist, who was a 6×6 driver for the wire section. I hadn’t known him very well, as he probably avoided contact with the new ASTP (“quiz kids”) transferees, as did many of the Camp Maxie survivors. As our duty went by, though, we became good friends, and mutual admirers. For his own acceptance, he had taken on the persona of a tough New Jersey street kid. He really had much more class and sensitivity than his role in the battery permitted him to have. I knew a little French from college, and we chalked “Ca y est” on our truck which I think means “That’s It” , and it got us a little extra admiration from the newly liberated French, who crowded around the trucks at rest stops. We drove from Normandy beaches, which became supply depots, to the railheads in Paris, where the supplies were hauled to the front. The countryside between Normandy and Paris was a mess and the railroads were out of order, but the roads, bad enough, were bulldozed clear and repaired for the trucks and other traffic. After leaving Paris, the Germans got out of France fast, and headed for the Sigfried line in Germany, so they didn’t take time to completely ruin the railroads between Paris and the front; hence they could carry the supplies from Paris. We seldom rested. We slept in the truck most of the time. At Omaha Beach it was so muddy we couldn’t get out of the trucks, and spent the night in them. They’d load us up in the morning, or whenever they had supplies ready, and off we’d go in convoys to the Paris railheads. One day to our surprise we suddenly had about a 24 hour rest period, so a couple of us went (AWOL) to Paris to explore. A French army truck picked us up–my buddy and I had three other GIs from somewhere—and someone had some brandy, which we shared. In fifteen minutes we were all singing, on into Paris. I won’t tell you everything about that evening, but one place we found ourselves was a nice little sort of dance nightclub, many of whose patrons were GI officers and men. The corny little band played “Sweet Sue” about every six numbers, to show off their American repertoire. Next morning we hitch hiked back to our chateau. How we knew how to get there I have no idea. Then we were back on the road. The interlude on the Red Ball Express was quite an experience for a 21-year-old; like no other in my life. And it ended my acceptance of the army warning “Never volunteer for anything”!

We members of this particular trucking group, were taken back to the Motor Pools apparently near the Normandy Beaches where we had landed; there were trucks and jeeps and every vehicle I had ever seen in the Army parked side by side and row on row, in the fields there. We were taken to the area that contained the 2 1/1 ton trucks, told to get them and drive them to a certain point (I can’t remember the exact location). The trucks didn’t even have the driver’s seats installed nor the cosmoline removed from the metal parts. We had to dig the seats out from the truck beds uncrate them and install them before we could drive out. M.Ps. were stationed at intersections where we were to make turns and in cities and towns to direct us through those areas. I remember some streets were so narrow that we had to make the second try to get around the street corners. I have noted that stories about the Red Ball Highway usually say the the highway was manned mostly by Black Soldiers. This may have been true later but the first two companies of drivers had no Black Soldiers as drivers. They did much of the work around the motor pools and the loading of trucks at that time. They well may have taken over the work of driving after our companies were disolved. Segragation was still practiced in the Service at that time. I mean no disrespect to the Black Soldier; they proved themselves capable of great feats in that, and in successive wars, I’m sure. I saw many German Prisoners of War around the dock and motor poole areas. I’m not sure what their work was but they were there in pretty large numbers. I remember them singing as they marched from place to place. We had three drivers assigned to a truck. We had a drop off point where the oldest man would leave the truck and we would take on the rested man; on the way back this would be repeated. This way, we kept the trucks moving. The first company of drivers seemed to be made up of regular drivers from their various units; the second made up of assistant drivers. I think from there on they tapped anyone who they thought could drive. There were many accidents. We had four flat tires on one trip. The enemy had cut horseshoes in two at the toe and strewed them on the highway. When a tire hit them, they would almost invariably flip up and penetrate the tire and cause an immediate flat. Wires stretched across the highway killed several men before our people devised a method of cutting the wire; a length of angle iron with a notch at the top to catch and cut the wire, was welded to the front bumper of each vehicle. But, I think you probably know most of what I’m writing so this may be boring to you. I ended up becoming a POW myself. Captured near Nancy, France, and held until May of 45.

Sincerely,

Paul G. Beckett